Organizations and their effectiveness-2016/Key concept definitions

Our collective homework for Tuesday, July 5...

Identity

Melissa

Social identity is a person's sense of who they are based on their group membership(s). Different social identities become more or less salient in different situations.

"I'm a Googler" "I was a Stanford undergrad" "I'm an economist" "I'm on the alpha project team"

You might care about it because... people's self-categorization with a particular group "brings self-perception and behavior in line with the contextually relevant ingroup prototype. It produces, for instance, normative behavior, stereotyping, ethnocentrism, positive ingroup attitudes and cohesion, cooperation and altruism, emotional contagion and empathy, collective behavior, shared norms, and mutual influence." (Hogg and Terry 2000, pg. 123 - attached)

Consuelo

I like James Fearon’s discussion of identity:

“As we use it now, an “identity” refer to either (a) a social category, defined by membership rules and (alleged) characteristic attributes or expected behaviors, or (b) socially distinguishing features that a person takes a special pride in or views as unchangeable but socially consequential (or (a) and (b) at once).

In the latter sense, “identity” is modern formulation of dignity, pride, or honor that implicitly links these to social categories. This statement differs from and is more concrete than standard glosses offered by political scientists; I argue in addition that it allows us to better understand how “identity” can help explain political actions, and the meaning of claims such as “identities are socially constructed.” … I argue that ordinary language analysis is a valuable and perhaps essential tool in the clarification of social science concepts that have strong roots in everyday speech, a very common occurrence.”

Here are other definitions of identity in political science (from Fearon 1999): 1. Identity is “people’s concepts of who they are, of what sort of people they are, and how they relate to others” (Hogg and Abrams 1988, 2).

2. “Identity is used in this book to describe the way individuals and groups define themselves and are defined by others on the basis of race, ethnicity, religion, language, and culture” (Deng 1995, 1).

3. Identity “refers to the ways in which individuals and collectivities are distinguished in their social relations with other individuals and collectivities” (Jenkins 1996, 4).

4. “National identity describes that condition in which a mass of people have made the same identification with national symbols – have internalized the symbols of the nation ...” (Bloom 1990, 52).

5. Identities are “relatively stable, role-specific understandings and expectations about self” (Wendt 1992, 397).

6. “Social identities are sets of meanings that an actor attributes to itself while taking the perspective of others, that is, as a social object. ... [Social identities are] at once cognitive schemas that enable an actor to determine ‘who I am/we are’ in a situation and positions in a social role structure of shared understandings and expectations” (Wendt 1994, 395).

7. “By social identity, I mean the desire for group distinction, dignity, and place within historically specific discourses (or frames of understanding) about the character, structure, and boundaries of the polity and the economy” (Herrigel 1993, 371).

8. “The term [identity] (by convention) references mutually constructed and evolving images of self and other” (Katzenstein 1996, 59).

9. “Identities are ... prescriptive representations of political actors themselves and of their relationships to each other” (Kowert and Legro 1996, 453).

10. “My identity is defined by the commitments and identifications which provide the frame or horizon within which I can try to determine from case to case what is good, or valuable, or what ought to be done, or what I endorse or oppose” (Taylor 1989, 27).

11. “Yet what if identity is conceived not as a boundary to be maintained but as a nexus of relations and transactions actively engaging a subject?” (Clifford 1988, 344).

12. “Identity is any source of action not explicable from biophysical regularities, and to which observers can attribute meaning” (White 1992, 6).

13. “Indeed, identity is objectively defined as location in a certain world and can be subjectively appropriated only along with that world. ... [A] coherent identity in- corporates within itself all the various internalized roles and attitudes.” (Berger and Luckmann 1966, 132).

14. “Identity emerges as a kind of unsettled space, or an unresolved question in that space, between a number of intersecting discourses. ... [Until recently, we have incorrectly thought that identity is] a kind of fixed point of thought and being, a ground of action ... the logic of something like a ‘true self.’ ... [But] Identity is a process, identity is split. Identity is not a fixed point but an ambivalent point. Identity is also the relationship of the Other to oneself” (Hall 1989).6

Examples:

“Students of American politics have devoted much new research to the “identity politics” of race, gender and sexuality. In comparative politics, “identity” plays a central role in work on nationalism and ethnic conflict (Horowitz 1985; Smith 1991; Deng 1995; Laitin 1999). In international relations, the idea of “state identity” is at the heart of constructivist critiques of realism and analyses of state sovereignty (Wendt 1992; Wendt 1999; Katzenstein 1996; Lapid and Kratochwil 1996; Biersteker and Weber 1996). And in political theory, questions of “identity” mark numerous arguments on gender, sexuality, nationality, ethnicity, and culture in relation to liberalism and its alternatives (Young 1990; Connolly 1991; Kymlicka 1995; Miller 1995; Taylor 1989)” (Fearon 1999, 1)

Credibility

Bo

Credibility: Reputation system works so well, I don't need conditional contracts or monitoring.

Culture

Dan W

Definition: An enduring system of widespread beliefs and values in a given society that guides individuals’ expectations and behavior in everyday social life. (Inspired by: Geertz (1973), DiMaggio and Powell (1983), Morris (2015))

Important elements of my definition:

- “enduring” - culture can change, but it changes slowly.

- “widespread beliefs and values” - subjective notions about what is appropriate behavior and important to living a good life (in Cicero’s sense!) that are shared by some non-trivial proportion of a bounded population.

- “guides” - important that culture only guides instead of enforcing conformity. People have various degrees of attachment to a given culture.

- “expectations” - how one ought to feel about a certain action based on what is appropriate in a given culture.

- “everyday social life” - culture pervades every social interaction because it delineates the terms by which we come to a shared understanding through communication.

Example:

- Guiso, Pistaferri, and Schivardi (2015) (EIEF Working Paper 1512) — How might one detect culture? Well, here's how. The authors in this paper find that Italian adults who moved from a more entrepreneurial region (i.e., higher % self-employed) to a less entrepreneurial region (i.e., lower % self-employed) as adolescents are more likely to become entrepreneurs than the average resident of the current less entrepreneurial region in which they live.

Bob

As mentioned last week, I would distinguish between an external culture that might seep into an organization versus an organizational culture that might arise or be built within an organization. See the Martinez et al. (2015) short essay in AER P&P from the readings for my second session for more on this distinction. On the former, in addition to the Hofstede (1980) and Bloom, Sadun, and Van Reenen (2012) papers mentioned last week and cited in Martinez et al., there is also Ichino and Maggi (QJE 2000) about absenteeism by Northern and Southern Italians who move between northern and southern branches of a large Italian bank. On the latter, Schein (1985) is a key reference and gives a definition of organizational culture quoted in Martinez et al., and I would offer the unpublished paper mentioned last week by the Martinez team plus additional co-authors as first-differenced evidence: analyzing ICUs in Michigan in 2004 and again in 2006, the bloodstream-infection rate fell the most in ICUs where the nurses' answer improved the most to the statement "I frequently have trouble expressing disagreement with staff physicians in this ICU."

Bo

Culture: Collection of norms, see above.

Norm: We are in a relational contract that grants us both discretion. But we usually follow some rule (the norm) even though we technically have discretion to do whatever. Following the norm decreases our coordination costs.

Network

Dan W

Definition: A non-random set of meaningful relationships distributed among individuals (or organizations, or any other purposive entities) that together do not reduce to the aggregate properties of those connected individuals (Inspired by: Scott (1991) -- the one and only textbook on social networks anyone ever needs!).

Important elements of my definition:

- “non-random” - social relationships emerge between entities in a social environment for some articulable, and often observable, reason.

- “meaningful” - a set of relationships that contributes interpretive richness to the entities connected by those relationships beyond their individual characteristics.

- “purposive” - entities connected by network relationships have their own desires which are sometimes liberated and sometimes shackled depending on the pattern, strength, and nature of the networks in which they are embedded.

Example:

- What does a real network look like with real consequences? Padgett and McLean (2006) show that a centuries-long intermarriage network between families representing different guilds after the Ciompi revolt around the time of Renaissance Florence redefined the economic and social actions of those families, giving birth to the partnership system of economic organization

Romain

Definition: a network is a collection of nodes and a collection of ties among these nodes.

Types of networks: Several common distinctions are often made when talking about networks. A network can be directed or undirected (tie from $i$ to $j \neq$ tie from $j$ to $i$), and weighted or unweighted. One can also consider static vs. dynamic networks (ties or nodes are created/disappear over time), or multiplex networks (there are several types of ties).

When talking about networks, one should always define: (1) what type of network are we talking about, (2) what is a node, (3) what is a tie. Examples: friendship network [type = undirected, unweighted network, node = person, tie = $i$ and $j$ are friends], airport traffic [type = weighted, directed network, node = airport, tie = number of daily flights from airport $i$ to airport $j$]

(Theoretical) network models: Two broad distinctions: (1) network formation vs. process on a network, (2) non-strategic [no game theory] vs. strategic [game theory].

Examples:

Non-strategic game of network formation: Barabassi and Albert's model of preferential attachment. Question: Why do networks often exhibit a hub and spoke structure [few nodes with many connections, many nodes with few connections]? Model: start with one node. At each time period, a new node is created and forms 1 tie with some old node selected at random. Old nodes with more connections are selected with higher probability.

Strategic game of network formation: Matt Jackson's coauthor's model. Question: how does a population of scholars pick coauthors? Authors choose whether to form ties with other authors. Two authors with a tie are coauthors. Players' utility increases with the number of coauthors, but busy coauthors (ie coauthors with many connections) give less benefits less than non-busy coauthors.

Non-strategic process on a network: probabilistic diffusion model. Some disease diffuses on a network. Question: which structures lead to a pandemic (everybody is infected), which do not? On a network, an initial node is infected (the seed). She infects her neighbors with some probability. At each time period, newly infected nodes infect their neighbors with some probability.

Strategic process on a network: Chwe's model of social movements. Question: which network structures lead to a revolution (every node protests)? On a network, each node has a threshold. A node protests if the number of her neighbors who protest is above that threshold.

Power

Dan W

Definition: The probability that one can carry out some desire on the basis of resource dependence, legitimacy, or normative commitment in a social setting despite potential resistance to that desire. (Inspired by: Weber (1905), Cook and Emerson (1983))

Important elements of my definition:

- “social setting” - power is only meaningful when one can exercise it over at least one other person.

- “potential resistance” - the other party in a social setting need not actively resist the use of power for power to be manifest.

- “resource dependence” - Source #1 of power: the other party depends on a focal individual for some resource, which is why the focal individual can exercise power despite the other party’s resistance.

- “legitimacy” - Source #2 of power: the other party acknowledges the widespread legitimacy of the focal individual’s power, even if the other party disagrees with the individual’s use of it.

- “normative commitment” - Source #3 of power: the other party disavows the legitimacy of an individual’s power and does not rely on the individual for some resource, but can exercise no real challenge because the individual’s incumbency is woven into the very norms that guide social action.

Example:

- All of Dan Carpenter's readings??

Mara

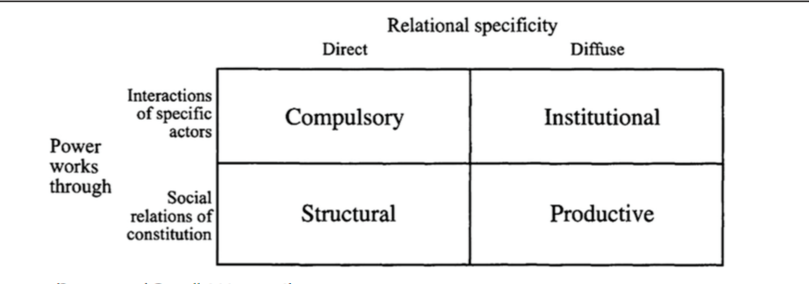

Power is the #1 obsession in IR, so it's difficult to formulate a one-sentence definition. But roughly, I think the various understanding of power can be distilled along two dimensions.

1) "Materialist/Agentic": in the sense that power is something agents possess and exert; having “power over”

- The most famous example here is Dahl’s (1957) definition: power is “power is the ability of A to get B to do something he or she would otherwise not do”

However, this reflects a rather limited conception since it views power as: agentic; direct (A acts on B); intentional (A means to do something to B); compulsive/coercive; and requiring a change in behavior, which assumes that the effects of power will be observable & measurable.

To address some of these limitations, we can bring in a second dimension of power

2) "Relational/Constitutive": power is something that creates agents and defines them in relation to one another; having “power to”.

- The best summary here is Barnett & Duvall (2005), who develop a 2x2 typology:

- "Compulsory power": direct control by one actor over another in relations of interaction (Dahlian power)

- "Institutional power": control actors exercise over others indirectly & diffusely over within formal & informal institutions—i.e. exercise of power via institutional rules that prescribe and proscribe certain conduct; actors control others in indirect ways (ex. agenda-setting power)

- "Structural power": constitution of subjects’ identities, capacities and interests in direct, dialectic social relation to one another (e.g. master/slave dialectic, civilized/uncivilized) (Hegel)

- "Productive power": socially-diffuse production of subjectivity in systems of meaning and signification that shapes all actors alike in their environment (not in direct relation to one another)—i.e. constitution of all subjects together through various systems of knowledge and discursive practices, and networks of social forces perpetually shaping one another (e.g. categories like “civilized” or “terrorist”) (Foucault)

Mike

This is not a formal definition, but it is illustrative of how some economists think about power. In a situation in which there are two or more people with conflicting preferences over a decision to be made, a person has "all the power" if their preferred decision is made. Compromises can of course result in decisions that are not the preferred decision of any person involved, so in many situation, nobody has "all the power." (Though according to this definition, in any single-person decision problem, the decision-maker has "all the power.") A person has "more power" if the decision made is something they prefer to the decision that would be made if they had "less power."

Sources of power in economics: (1) patience and risk tolerance in bargaining (these are the standard components of "bargaining power" in models of bargaining), (2) information (for a particularly clear illustration, see Aghion and Tirole (1997) on "real authority" in which a formal decision-maker makes my preferred decision if I am informed, she is not, and she prefers making my recommended decision to inaction or taking a stab in the dark. Models of delegation, going back to at least Simon (1951)--although I'm not sure others view his model as a model of delegation, are also relevant here.), (3) possession of legally granted control rights (see Grossman and Hart (1986) and Hart and Moore (1990) for a clean operationalization), (4) commitment power (this is akin to the "first-mover advantage," and it begs the question of where commitment power comes from), (5) rewards for past performance (see Li, Matouschek, and Powell (2016)).

Utility

John Stuart Mill

The principle of utility describes "actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness; wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain and the privation of pleasure."

Bo

Rational and Utility: Rational: An agent who is attempting to optimize something. Could be anything. Please note that someone can be attempting to optimize the "wrong" variable, or might be using "wrong" information in their optimization -- and they can still be rational. Utility: Whatever is being optimized above. Given this, the two definitions directly above are arguably so broad to be unfalsifiable. Fair point! The purpose is to justify mathematics of optimization being applied to behavior.

Romain

Real-valued function representing preferences over choices. That is, suppose there are many alternatives $x_1, ..., x_n$. Suppose I have well-defined preferences over those choices (that is, for each pair of choices, I can say which one I prefer). A utility function is a function over those choices is function such that if I prefer $x_i$ to $x_j$, then $u(x_i) \geq u(x_j)$.

Mike

Utility is just a representation of an individual's preferences. If the preferences are well-behaved, then utility can be represented as a continuous function (as Romain describes above). We like preferences that can be represented by a utility function, because then the notion of "optimal choice" is well-defined (as long as the set of things the individual can choose from is well-behaved).

On the board, it said, "utility (with no condition)," presumably referring to the use of the word in sentences like, "Choice A gives him more utility than choice B." This is just another way to that the individual prefers A to B.

Note that preferences are defined on the set of all possible choices and not just on the set of choices that are feasible to the decision maker. Also, utility functions do not need to always be increasing--representing preferences with a utility function does not imply that "more is always better."

Rationality

Romain

I am rational when I select the choice that maximizes my utility.

Manuel

Definition: Coherent utility maximization given a certain utility function and situational constraints.

Examples: Expected utility theory (von Neumann & Morgenstern, 1944) but potentially also less obvious candidates like satisficing (Simon, 1956). Often things that look irrational at first sight are not.

Mike

Definition (formal): An individual's preferences are rational if they are complete (meaning that for any two outcomes, one is preferred to the other, or neither is preferred to the other) and transitive (meaning that if cows are preferred to telephones, and telephones are preferred to Wonder Bread, then cows are preferred to Wonder Bread). This is the standard definition that comes up in any graduate-level microeconomics textbook (such as Mas-Collel, Whinston, and Green).

Definition (less formal): An individual choice is rational if we can think of it coming from a cost-benefit analysis made by the decision maker. This cost-benefit analysis does not need to be made consciously, and this definition does not require that the decision maker not make any mistakes. It just means that the decision maker does not systematically make decisions she knows are a bad idea (in the sense that, according to whatever preferences she has, she does not systematically make decisions for which the costs outweigh the benefits). The costs and benefits of the decision do not need to be immediate, financial, or even concrete.

Tastes

Bo

Tastes: Someone's private likes and dislikes. There is no "correct" taste.

Manuel

Definition: Preferences that are inherent to an individual and that are in some way exogenously given, that is their source cannot be further tracked down or their specific shape truly explained. It is therefore useless to discuss about the nature of a set of (coherent) preferences: “de gustibus non est disputandum”. We simply have to accept them as given.

Examples: Gary Becker’s (1957) taste-based discrimination model is probably the most striking (and controversial) example.

Trust

Manuel

Definition: Willingness to rely on (and make oneself vulnerable to) the actions of another person because of a belief that the other person will honor this leap of faith and act in ways that benefit the relationship (and not only according to pure monetary self-interest). Note: this definition of trust differs from "economic trust" in repeated games, in which trust is sustained via the benefits of future cooperation.

Examples: Trust game (Berg, Dickhaut & McCabe, 1995 Games and Econ Behav) or gift-exchange literature (Akerlof, 1982 QJE; Fehr, Kirchsteiger & Riedl, 1993 QJE)

Bob

I agree that it is important to save "trust" to mean something beyond the purely consequentialist logic sometimes called "calculative trust" in repeated games. Last week I called the repeated-game argument "assurance," following Yamagishi and Yamagishi (1994). See the Gibbons-Henderson (Org. Sci. 2012) reading from my second session last week for more discussion and references, as well as quarter-baked queries about whether the consequentialist logic might complement or crowd out real trust.

That said, I think trust and assurance remain hard to separate, at least for me. For example, to my eye, the first part of Manuel's definition applies to both: "Willingness to rely on (and make oneself vulnerable to) the actions of another person because of a belief that the other person will honor this leap of faith and act in ways that benefit the relationship." It is the second part that then distinguishes between the two -- namely, " (and not only according to pure monetary self-interest)" -- although I would delete "monetary" from this phrase because there are of course repeated-game arguments that are entirely consequentialist but do not involve money (such as a repeated PD).

So I guess I have moved from needing one definition to needing another: if you and I are playing a two-move game and I play "trust" in my first move (and it is common knowledge that the game is definitely over after your second move, and that we will never see each other again, and that you will never interact with third parties who knowhow you played in our game), is it the same thing to say (a) that I am trusting you and (b) that I have a view about your "type" that leads me to predict how you will act after I play "trust"?

Bo

Trust: Reputation system works so well, I don't need monitoring or contracts.

Rationalization

Manuel

Definition (as a research approach): Explaining observed behavior via a rational utility maximization (“functionalist”) account.

Examples: Again taste-based discrimination (Becker, 1957), but also recent models of self-confidence (e.g., Bénabou & Tirole, 2002 QJE), ego-utility (Koszegi, 2006 JEEA) or reference-dependence (Koszegi & Rabin, 2006 QJE).

Woody

Rationalization also draws directly from Weber, and his discussion in the The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism of the disenchantment of the world. There he was talking about the replacement of tradition and charisma by calculability. Weber’s image of the iron cage – the idea that humans have become trapped in a system of technocratic thinking and rational calculation – suggests that calculable, methodical, and instrumental forms of organizing are expanding into more and more domains of modern life.

For readings, see Bendix 1956, in a masterful mid-20th century assessment of managerial ideologies, he describes the bureaucratization of management clearly: “The increasing size of industrial enterprises entails certain administrative problems which in each case require for their solution the addition of salaried personnel.” (p. 226) His analysis captures a secular change in the American industry by which entrepreneurs and heirs are replaced by better-educated bureaucrats. For the U.S. nonprofit sector, see Hwang and Powell, ASQ, 2009, where we show the adoption of strategic planning, external audits, and efficiency metrics related to admin. costs. Christof and i currently are working on a paper showing how and why the contents of rationalization change over time.

Rational

Bo

Rational: An agent who is attempting to optimize something. Could be anything. Please note that someone can be attempting to optimize the "wrong" variable, or might be using "wrong" information in their optimization -- and they can still be rational.

Utility: Whatever is being optimized above.

Given this, the two definitions directly above are arguably so broad to be unfalsifiable. Fair point!

The purpose is to justify mathematics of optimization being applied to behavior.

Legitimacy

Bo

Legitimacy: Our relational contract is an equilibrium that grants you discretion. I'm okay with that.

Mara

Thomas Franck’s (1988) is an international lawyer and I think this definition has some interesting implications for our discussions of formal and relations contracts. Franck defines legitimacy as “the quality of a rule which derives from a perception on the part of those to whom the rule is addressed that it has come into being in accordance with the right process”. He identifies four indicators of legitimacy:

- ”Determinacy”= clarity, letting people/states know exactly what is expected of them. The more determinant a rule, the more difficult to resist compliance and to justify non-compliance & the less room for “flexible” interpretation

- “Symbolic validation/ritual/pedigree”= for a rule to be legitimate, it needs to be able to communicate its authority—“the authority of the rule, the authority of the originator of a validating communication and, at times, the authority bestowed on the recipient of the communication.” It does this through:

- ”Symbolic validation”: when some kind of signal or act is used as a cue to elicit compliance with a command. The cue is a surrogate for articulating the reasons for obedience. Ex. a salute reinforces a soldier’s deference to his commander

- “Ritual”: a specific form of symbolic validation marked by ceremonies, often—but not necessarily—mystical, that provide unenunciated reasons or cues for eliciting compliance with the commands of persons or institutions…often presented as drama, to communicate to a community its unity, its values, its uniqueness in both the exclusive and inclusive sense”. Ex. taking community

- ”Pedigree”: “a subset of cues that seeks to enhance the compliance pull of rules or rule-making institutions by emphasizing their historical origin, their cultural or anthropological deep-rootedness”. Ex. the act of Parliament bringing a bill to the Queen for her approval

- ”Coherence”: “a rule is coherent when like cases are treated alike in application of the rule and when the rule relates in a principled fashion to other rules of the same system….requires that a rule, whatever its content, be applied uniformly in every ‘similar’ or ‘applicable’ instance.” Ex. in the US, we express this through tenets like “justice is blind” and “all men are equal before the law”

- ”Adherence” (to a normative hierarchy): “rules tend to achieve compliance when they, themselves, comply with secondary rules about how and by whom rules are to be made and interpreted” and these secondary rules, in turn, must comply with a “unifying rule of recognition” that “specifies the sources of law and provides criteria for the identification of its rules”, which is the ultimate authority (e.g. US Constitution)

Aaron

Even a lapsed sociologist knows only one place to turn when it comes to defining legitimacy: Weber! Here goes (in hyper-brief form):

- An acceptable relationship or exercise of authority.

Woody

Legitimacy is a challenging term to define. In sociology, following Weber, it refers to the right and acceptance of authority. But it can also be a resource, and there is an ample literature on negotiating and claiming legitimacy (see Marc Suchman, Managing Legitimacy, Acad Mgmt Rev July 1995). Suchman attempts to disentangle pragmatic, moral, and cognitive aspects of legitimacy. I tend to like the pragmatic and cognitive aspects, which suggest that behavior is perceived to be appropriate in a particular context.

There is a wonderfully rich discussion of legitimacy in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which if you don't know is a wonderful resource. i cut and paste a little snippet below:

Descriptive and Normative Concepts of Legitimacy If legitimacy is interpreted descriptively, it refers to people's beliefs about political authority and, sometimes, political obligations. In his sociology, Max Weber put forward a very influential account of legitimacy that excludes any recourse to normative criteria (Mommsen 1989: 20). According to Weber, that a political regime is legitimate means that its participants have certain beliefs or faith (“Legitimitätsglaube”) in regard to it: “the basis of every system of authority, and correspondingly of every kind of willingness to obey, is a belief, a belief by virtue of which persons exercising authority are lent prestige” (Weber 1964: 382). As is well known, Weber distinguishes among three main sources of legitimacy—understood as both the acceptance of authority and of the need to obey its commands. People may have faith in a particular political or social order because it has been there for a long time (tradition), because they have faith in the rulers (charisma), or because they trust its legality—specifically the rationality of the rule of law (Weber 1990 [1918]; 1964). Weber identifies legitimacy as an important explanatory category for social science, because faith in a particular social order produces social regularities that are more stable than those that result from the pursuit of self-interest or from habitual rule-following (Weber 1964: 124).

In contrast to Weber's descriptive concept, the normative concept of political legitimacy refers to some benchmark of acceptability or justification of political power or authority and—possibly—obligation. On the broadest view, legitimacy both explains why the use of political power by a particular body—a state, a government, or a democratic collective, for example—is permissible and why there is a pro tanto moral duty to obey its commands. On this view, if the conditions for legitimacy are not met, political institutions exercise power unjustifiably and the commands they might produce do then not entail any obligation to obey. John Rawls, in Political Liberalism (1993), presents such an interpretation of legitimacy.

On one widely held narrower view, legitimacy is linked to the moral justification—not the creation—of political authority. Political bodies such as states may be effective, or de facto, authorities, without being legitimate. They claim the right to rule and to create obligations to be obeyed, and as long as these claims are met with sufficient acquiescence, they are authoritative. Legitimate authority, on this view, differs from merely effective or de facto authority in that it actually holds the right to rule and creates political obligations (e.g. Raz 1986). According to an opposing view (e.g. Simmons 2001), political authority may be morally justified without being legitimate, but only legitimate authority generates political obligations.

Christof

Legitimacy, according to new institutionalist theory, is the perception of an organization as desirable, proper, and appropriate. Adopting legitimate policies or practices does not require justification, whereas not adopting them does. Legitimacy is granted by an “audience” (= institutional environment), which makes legitimacy an inherently relational concept. This definition goes beyond ideas of a regime’s legitimate authority (Weber 1978[1922]) and the public’s voluntary acquiescence to a government (Verba, Nie, and Ki 1979). According to Suchman (1995), the grounds on which an organization or action is considered legitimate can be pragmatic ("it works well"), moral ("it is the right thing to do"), and cognitive ("it’s how we do things"). For a more detailed definition, see Deephouse & Suchman 2008. Some organizational sociologists have worked to differentiate legitimacy from reputation and status (e.g. Bitektine 2011; King & Whetten 2008). Suddaby and Greenwood’s Rhetorical Strategies of Legitimacy is one study that links the concept of legitimacy to accounts as well as the jurisdictional struggles Beth Bechky discusses in Object Lessons.

Norms

Consuelo

A norm is a “shared standard of behavior appropriate for actors with a given identity” (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Florini 1996)

Example: Susan Hyde’s “Catch Us If You Can: Election Monitoring and International Norm Diffusion” (2011) On the norm of international election monitoring, Hyde concludes that “[t]he norm of election observation diffused widely because (1) international actors initiated and then increased democracy-contingent benefits, and (2) a government's commitment to democracy is difficult for democracy promoters to observe directly.”

Mara

Norms are intersubjective standards defining socially-appropriate behavior for a given type of actor in a given situation. They can have regulative, constitutive, permissive, prescriptive & proscriptive effects. Norms don't guarantee that agents will behave in certain ways; they only make certain behaviors more or less likely. Relatedly, norms are "counterfactually valid", meaning that specific incidences of non-compliance doesn't invalidate the norms (i.e. rules can be honored in the breach).

Russ

Social norms are informal rules that govern behavior in social groups. Honesty and reciprocity are common examples. Norms are an important mechanism for maintaining social order and facilitating cooperation. Deviation from norms is often met with sanctions, which may be informal (e.g., scorn) or formal (e.g., exclusion from the group). Robert Merton's classic article on "The Normative Structure of Science" offers a nice illustration of norms. In the article (attached), he argues that science is characterized by four norms:

Universalism---scientific contributions are evaluated independently of the person or persons who made them (e.g., anyone can potentially make a contribution to science)

Communism---scientific findings are the property of the community (i.e., there should be no private ownership of scientific knowledge)

Disinterestedness---science is done to advance the enterprise of science, not for the personal gain of contributors

organized skepticism---scientific claims should be subjected to criticism and scrutiny before being accepted

Bob

Can a repeated-game equilibrium be a norm? If so, are all norms such equilibria? How does this distinction relate to trust and socialization?

Bo

Norm: We are in a relational contract that grants us both discretion. But we usually follow some rule (the norm) even though we technically have discretion to do whatever. Following the norm decreases our coordination costs.

Functionalism

Russ

Functionalism (particularly structural functionalism), within sociology, is a perspective that social phenomena in terms of the function or purpose they serve. The perspective offers a very static picture of society. Moreover, it can be used to justify undesirable social phenomena (e.g., inequality) and therefore has been sharply criticized. The article, "Some Principles of Stratification" by Kingsley Davis and Wilbert E. Moore (1945) offers a good example. Davis and Moore argue that stratification (i.e., social classes) is functionally necessary in society to motivate people to do things that are important but would otherwise be undesirable, e.g., medical school: "Modem medicine, for example, is within the mental capacity of most individuals, but a medical education is so burdensome and expensive that virtually none would under- take it if the position of the M.D. did not carry a reward commensurate with the sacrifice."

Christof

Functionalism, in sociology, is an analytical framework that describes the world as a stable, cohesive system, whose parts contribute to the stability of the overall system. More simply, things are the way they are because they work. (Structural) functionalism was a dominant school of thought in 1950s sociology. The framework's legitimacy was compromised by an intellectual dispute between Harvard-sociologist Talcott Parsons and some of his colleagues (such as CW Mills). Anti-functionalists considered the framework inherently conservative, which they considered to be at odds with observed conflict, turmoil, and oppression in the real world. Critics of functionalism invoke what Gould and Lewontin called the Panglossian Paradigm as an illustration for the naïve assumptions underlying the idea that social structures must be functional. Dr. Pangloss, a "court meta-physician" in Voltaire’s play Candide, gave the paradigm its name: “It is demonstrable,” said [Dr. Pangloss], “that things cannot be otherwise than as they are; for as all things have been created for some end, they must necessarily be created for the best end. Observe, for instance, the nose is formed for spectacles, therefore we wear spectacles. The legs are visibly designed for stockings, accordingly we wear stockings. Stones were made to be hewn and to construct castles, therefore My Lord has a magnificent castle; for the greatest baron in the province ought to be the best lodged. Swine were intended to be eaten, therefore we eat pork all the year round: and they, who assert that everything is right, do not express themselves correctly; they should say that everything is best.”

There aren’t really any empirical studies of functionalism because it’s pretty much a non-falsifiable school of thought whose validity depends on what one considers “optimal” or “efficient." One eloquent critique of the functionalism of Transaction Cost Economics is Granovetter’s (1985) Economic Action and Social Structure, in which he challenges Williamson’s claim that “the organizational form observed in any situation is that which deals most efficiently with the cost of economics transactions”. Granovetter’s main concern is that selection pressures may be weak and efficient solutions may not be feasible, allowing for dysfunctional or second-best organizational designs.

Voice

Russ

Voice, as defined in Albert O. Hirschman's book, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (attached), is one of two options people (e.g., employees, customers, citizens) have in response to the declining performance of their organizations (e.g., employers, firms, states). In contrast to the other option, exit, in which a person dissolves his or her relationship with the organization, voice is an attempt to repair the relationship through criticism and feedback. Voice is potentially more informative for organizations because it gives reasons for declining performance, whereas exit is just an indicator. The book focuses on (among other things) determining when exit or voice is most likely to be used (e.g., when options for exit are higher, voice is likely lower; when people have loyalty to the organization, voice is likely higher).

As an interesting bit of context, the book was written while Hirschman was a fellow at CASBS: "This is an unpremeditated book. It has its origin in an observation on rail transport in Nigeria which occupied a paragraph in my previous book, reproduced here at the start of Chapter 4. One critic objected to that paragraph because, as he charitably expressed himself, 'there must be a lot of assumptions hidden there somewhere.' After a while I decided to pursue these assumptions into their hiding places and was soon on an absorbing expedition which lasted the full year that I had planned to spend in leisurely meditation at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences...The Center provided a particularly favorable environment for this sort of project. I made ample use of the 'right to buttonhole' the other Fellows which is, I believe, an essential part of the oral tradition at the Center. My intellectual debts to those who spent the year with me are generally acknowledged in footnote references. Special gratitude is owed to Gabriel Almond who contributed important critical points while being permanently supportive of my enterprise; to a comment by Richard Lowenthal that led me to write Chapter 6; and to Tjalling Koopmans 'who helped sharpen some of the technical arguments, as did Robert Wilson of the Stanford Business School."

Aaron

I also defined voice from Hirschman. In keeping with Bo's efforts to craft "tweetable" definitions, mine is the following:

- An attempt to maintain, improve, or repair relationships through communication (expression of dissent, frustration, agreement/support, commitment)

Bo

Voice: We are in a relational contract. The world changes. We both help choose the new equilibrium.

Contract

Aaron

I thought I'd try to go outside my comfort zone and define something I know little about. Building on Bob's definition (see his slides), here's my version of what a contract is:

- A formal or informal agreement that establishes or codifies shared expectations through the use of commitments and/or assurances.

Status

Bo

Status: Positive-sum game of deference (sometimes costly deference).

Accounts

Woody

I like the term accounts a lot. It has a discursive aspect, indeed, it has been used in a little literature on the sociology of talk (see Scott & Lyman, ASR, Feb. 1968). In this context, it refers to socially approved vocabularies, or statements made to bridge the gap between actions and expectations. P&P makes a great deal out of Renaissance account books, which detail social expectations quite clearly, and of course, double-entry bookkeeping is a topic that Padgett and Wargalien are writing about. Accounts are a linguistic or symbolic device employed when actions are subject to evaluative inquiries. There is an obvious link to be built to Gibbons' use of the term stories.

For an article on the evolution of the term "appropriate" in the context of academic entrepreneurship, see Colyvas and Powell, 20006. Roads to Institutionalization: The Remaking of Boundaries Between Public and Private Science (PDF), Research in Organizational Behavior, 21:305-53 (2006) Jeannette Colyvas, W.W. Powell.

Status

Christof

Status, in macro-organizational sociology, is an organization’s position in the social structure. Organizations higher up in the status order have more social ties to other organizations, or more ties to well networked affiliates. It is easier for well-connected organizations to accumulate resources and perform highly, which leads to the self-reproduction of status. This process is commonly referred to as accumulative advantage or “Matthew Effect" (Chen et al. 2012, Sauder, Lynn, and Podolny 2012). High-status across can stay on top of the status order because they can produce cheaper and sell more expensively, as both suppliers and consumers use status information as a proxy for expected quality and reliability (Podolny 2005). Podolny’s (2005) book Status Signals is an authoritative account of how organizational status affect consumers, producers, and market competition. There is a largely separate literature on the status of individuals and groups inside organizations in social psychology.

Melissa

Status and power are sometimes rolled together into the idea of social hierarchy. Social hierarchy is defined as “an implicit or explicit rank order of individuals or groups with respect to a valued social dimension” (Magee, and Galinsky, 2008, pg. 354). It is seen as a “pervasive reality of organizational and group life given differences across individuals and units in resource endowments such as capital, knowledge, authority, information, network relations, experience, charisma, etc.” (Bunderson, and Reagans, 2011, pg. 1183 - attached). I think I like Bob's better - who can exercise discretion

Change process

Melissa

I've used this term a few times in the workshop, but what I mean by it doesn't match the primary organizations literature on change processes. Using Bob's three views of organizations lens, I would characterize the literature to date as the top left - cool blue design - because it is focused mostly on cognition. (Ed Schien's essay summarizes the most popular theory - Kurt Lewin's unfreeze-change-refreeze framework)

My intended meaning relates more to the top right on Bob's diagram - red hot politics. There are many studies that relate to this intended meaning, but they are not neatly lumped into a change theory literature. Change process in this way of thinking relates to the interactions and conditions under which a role structure is changed.

Anytime a role structure is being changed, there is a possibility of status or power loss for at least one of the role groups.

In a constructive change process, there is a predefined agreed-on fair process for how this will get worked out. Like hiring decisions in an acadmic department - one sub-group hiring disrupts the balance of power in the department, but if everyone has agreed that every sub-group gets a turn to hire round-robin, then the hiring process will go smoothly and at the end, everyone will have gotten a turn. The key here is "procedural justice" - the process, whatever it is, has to be agreed upon as fair so that everyone will accept an outcome that isn't their own best outcome.

But there are many other ways a role structure can change. Think of Kate's study. The defenders felt that the new hand-off practice was a threat to their status (i.e., other roles in the role structure would have gained footing and they would have lost footing) so they fought the change. The reformers had to hide in the free space and figure out how to work around the defenders to get the change they wanted.

As another example, in my second ER study, the change to organize nurses and doctors into pods was handled differently at different ERs. At one ER, there were many cross-occupational town halls where everyone got to brainstorm, ask questions, air grievances, etc. Then they piloted the pods and had more town halls to talk about what had happened and made adjustments and piloted them again. At another one, the ER medical director asked for feedback one time in single occupational groups and then (according to the residents and nurses) ignored the feedback and did what he wanted anyway. All communication came down in silos. Unsurprisingly, the first ER got to a new equilibrium and the second one did not. The change process was not seen as fair and it didn't give people a change to co-construct a new role structure that worked for everyone.

I'm going to think more about how to summarize the conditions and interactions across all these diverse studies, there's got to be a general framework here. Can post more on that later.