Community Data Science Course (Spring 2017)/Day 1 Tutorial: Difference between revisions

made tutorial |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 314: | Line 314: | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

<li>Download the file http://mako.cc/teaching/2014/cdsw/nobel.py by right-clicking on it and saying to save it as a ".py" file to your Desktop. The ".py" extension hints that this is a Python script.</li> | <li>Download the file http://mako.cc/teaching/2014/cdsw/nobel.py by right-clicking on it and saying to save it as a ".py" file to your Desktop. The ".py" extension hints that this is a Python script.</li> | ||

<li>Open a terminal prompt, and use the navigation commands ( | <li>Open a terminal prompt, and use the navigation commands (<code>ls</code> and <code>cd</code>) to navigate to your Desktop directory. | ||

<li>Once you are in your Desktop directory, execute the contents of <code>nobel.py</code> by typing | <li>Once you are in your Desktop directory, execute the contents of <code>nobel.py</code> by typing | ||

| Line 323: | Line 323: | ||

<code>nobel.py</code> introduces two new concepts: comments and multiline strings.</li> | <code>nobel.py</code> introduces two new concepts: comments and multiline strings.</li> | ||

<li>Open <code>nobel.py</code> in your text editor | <li>Open <code>nobel.py</code> in your text editor.</li> | ||

<li>Read through the file in your text editor carefully and check your understanding of both the comments and the code.</li> | <li>Read through the file in your text editor carefully and check your understanding of both the comments and the code.</li> | ||

</ol> | </ol> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:40, 4 April 2019

Welcome to the first tutorial!

This tutorial covers several core programming concepts that we'll build upon during an interactive lecture tomorrow morning. It will take 1-2 hours to complete. There's a break in the middle, and exercises at the middle and end to help review the material.

This is an interactive tutorial! As you go through this tutorial, any time you see something that looks like this:

a = "Hello"

you should type the expression at a Python prompt, hitting Return after every line and noting the output.

No copying and pasting! You'll learn the concepts better if you type them out yourself.

Math[edit]

Math in Python looks a lot like math you type into a calculator. A Python prompt makes a great calculator if you need to crunch some numbers and don't have a good calculator handy.

Addition[edit]

2 + 2 1.5 + 2.25

Subtraction[edit]

4 - 2 100 - .5 0 - 2

Multiplication[edit]

2 * 3

Division[edit]

4 / 2 1 / 2

If you were doing some baking and needed to add 3/4 of a cup of flour and 1/4 of a cup of flour, we know in our heads that 3/4 + 1/4 = 1 cup. Try that at the Python prompt:

3/4 + 1/4

Types[edit]

There's a helpful function (more on what a function is in a second) called type that tells you what kind of thing -- what data type -- Python thinks something is. We can check for ourselves that Python considers '1' and '1.0' to be different data types:

type(1) type(1.0)

So now we've seen two data types: integers and floats.

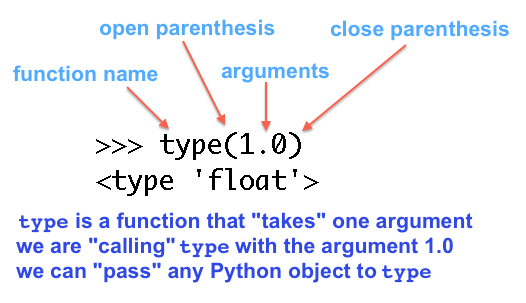

By the way, what is a "function"? Here are the important ideas about functions:

- A function encapsulates a useful bit of work and gives that work a name.

- You provide input to a function and it produces output. For example, the

typefunction takes data as an input, and produces what type of data the data is (e.g. an integer or a float) as output. - To use a function, write the name of the function, followed by an open parenthesis, then what the function needs as input (we call that input the arguments to the function), and then a close parenthesis.

- Programmers have a lot of slang around functions. They'll say that functions "take" arguments, or that they "give" or "pass" arguments to a function. "call" and "invoke" are both synonyms for using a function.

In the example above, "type" was the name of the function. type takes one argument; we first gave type an argument of 1 and then gave it an argument of 1.0.

Diagram of "calling" a function[edit]

Command history[edit]

Stop here and try hitting the Up arrow on your keyboard a few times. The Python interpreter saves a history of what you've entered, so you can arrow up to old commands and hit Return to re-run them!

Variables[edit]

A lot of work gets done in Python using variables. Variables are a lot like the variables in math class, except that in Python variables can be of any data type, not just numbers.

type(4) x = 4 x type(x) 2 * x

Giving a name to something, so that you can refer to it by that name, is called assignment. Above, we assigned the name 'x' to 4, and after that we can use x wherever we want to use the number 4.

Variables can't have spaces or other special characters, and they need to start with a letter. Here are some valid variable names:

magic_number = 1500

amountOfFlour = .75

my_name = "Jessica"

Projects develop naming conventions: maybe multi-word variable names use underscores (like magic_number), or "camel case" (like amountOfFlour). The most

important thing is to be consistent within a project, because it makes the code more readable.

Output[edit]

Notice how if you type a 4 and hit enter, the Python interpreter spits a 4 back out:

4

But if you assign 4 to a variable, nothing is printed:

x = 4

You can think of it as that something needs to get the output. Without an assignment, the winner is the screen. With assignment, the output goes to the variable.

You can reassign variables if you want:

x = 4 x x = 5 x

Sometimes reassigning a variable is an accident and causes bugs in programs.

x = 3 y = 4 x * y x * x 2 * x - 1 * y

Order of operations works pretty much like how you learned in school. If you're unsure of an ordering, you can add parentheses like on a calculator:

(2 * x) - (1 * y)

Note that the spacing doesn't matter:

x = 4

and

x=4

are both valid Python and mean the same thing.

(2 * x) - (1 * y)

and

(2*x)-(1*y)

are also both valid and mean the same thing. You should strive to be consistent with whatever spacing you like or a job requires, since it makes reading the code easier.

You aren't cheating and skipping typing these exercises out, are you? Good! :)

Strings[edit]

So far we've seen two data types: integers and floats. Another useful data type is a string, which is just what Python calls a bunch of characters (like numbers, letters, whitespace, and punctuation) put together. Strings are indicated by being surrounded by quotes:

"Hello" "Python, I'm your #1 fan!"

Like with the math data types above, we can use the type function to check the type of strings:

type("Hello")

type(1)

type("1")

String Concatenation[edit]

You can smoosh strings together (called "concatenation") using the '+' sign:

"Hello" + "World"

name = "Jessica" "Hello " + name

How about concatenating different data types?

"Hello" + 1

Hey now! The output from the previous example was really different and interesting; let's break down exactly what happened:

>>> "Hello" + 1

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: cannot concatenate 'str' and 'int' objects

Python is giving us a traceback. A traceback is details on what was happening when Python encountered an Exception or Error -- something it doesn't know how to handle.

There are many kinds of Python errors, with descriptive names to help us humans understand what went wrong. In this case we are getting a TypeError: we tried to do some operation on a data type that isn't supported for that data type.

Python gives us a helpful error message as part of the TypeError:

"cannot concatenate 'str' and 'int' objects"

We saw above the we can concatenate strings:

"Hello" + "World"

works just fine.

However,

"Hello" + 1

produces a TypeError. We are telling Python to concatenate a string and an integer, and that's not something Python understands how to do.

We can convert an integer into a string ourselves, using the str function:

"Hello" + str(1)

Like the type function from before, the str function takes 1 argument. In the above example it took the integer 1. str takes a Python object as input and produces a string version of that input as output.

String length[edit]

There's another useful function that works on strings called len. len returns the length of a string as an integer:

len("Hello")

len("")

fish = "humuhumunukunukuapua'a"

name_length = len(fish)

fish + " is a Hawaiian fish whose name is " + str(name_length) + " characters long."

Quotes[edit]

We've been using double quotes around our strings, but you can use either double or single quotes:

'Hello' "Hello"

Like with spacing above, use whichever quotes make the most sense for you, but be consistent.

You do have to be careful about using quotes inside of strings:

'I'm a happy camper'

This gives us another traceback, for a new kind of error, a SyntaxError. When Python looks at that expression, it sees the string 'I' and then

m a happy camper'

which it doesn't understand -- it's not 'valid' Python. Those letters aren't variables (we haven't assigned them to anything), and that trailing quote isn't balanced. So it raises a SyntaxError.

We can use double quotes to avoid this problem:

"I'm a happy camper"

One fun thing about strings in Python is that you can multiply them:

"A" * 40 "ABC" * 12 h = "Happy" b = "Birthday" (h + b) * 10

Part 1 Practice[edit]

Read the following expressions, but don't execute them. Guess what the output will be. After you've made a guess, copy and paste the expressions at a Python prompt and check your guess.

1.

total = 1.5 - 1/2 total type(total)

2.

a = "quick" b = "brown" c = "fox jumps over the lazy dog" "The " + a * 3 + " " + b * 3 + " " + c

End of Part 1[edit]

Congratulations! You've learned about and practiced math, strings, variables, data types, exceptions, tracebacks, and executing Python from the Python prompt.

Take a break, stretch, meet some neighbors, and ask the staff if you have any questions about this material.

Part 2: Printing[edit]

So far we've been learning at the interactive Python interpreter. When you are working at the interpreter, any work that you do gets printed to the screen. For example:

h = "Hello" w = "World" h + w

will display "HelloWorld".

Another place that we will be writing Python code is in a file. When we run Python code from a file instead of interactively, we don't get work printed to the screen for free. We have to tell Python to print the information to the screen. The way we do this is with the print function. Here's how it works:

h = "Hello" w = "World" print(h + w)

my_string = "Alpha " + "Beta " + "Gamma " + "Delta" print(my_string)

The string manipulate is exactly the same as before. The only difference is that you need to use print to print results to the screen:

h + w

becomes

print(h + w)

We'll see more examples of the print function in the next section.

Python scripts[edit]

Until now we've been using the interactive Python interpreter. This is great for learning and experimenting, but you can't easily save or edit your work. For bigger projects, we'll write our Python code in a file. Let's get some practice with this!

- Download the file http://mako.cc/teaching/2014/cdsw/nobel.py by right-clicking on it and saying to save it as a ".py" file to your Desktop. The ".py" extension hints that this is a Python script.

- Open a terminal prompt, and use the navigation commands (

lsandcd) to navigate to your Desktop directory. - Once you are in your Desktop directory, execute the contents of

nobel.pyby typing python nobel.py at the terminal prompt.nobel.pyintroduces two new concepts: comments and multiline strings. - Open

nobel.pyin your text editor. - Read through the file in your text editor carefully and check your understanding of both the comments and the code.

Study the script until you can answer these questions:

- How do you comment code in Python?

- How do you print just a newline?

- How do you print a multi-line string so that whitespace is preserved?

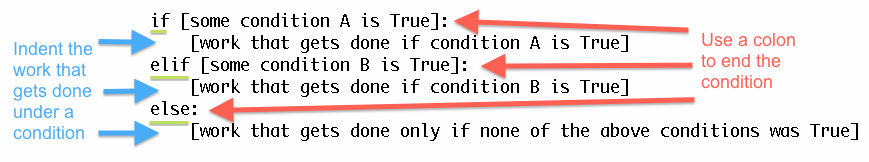

Making choices[edit]

We can use these expressions that evaluate to booleans to make decisions and conditionally execute code.

if statements[edit]

The simplest way to make a choice in Python is with the if keyword. Here's an example (don't try to type this one, just look at it for now):

if 6 > 5:

print("Six is greater than five!")

That is our first multi-line piece of code, and the way to type it at a Python prompt is a little different. Let's break down how to do this (type this out step by step):

- First, type the

if 6 > 5:

part, and press Enter. The next line will have...as a prompt, instead of the usual>>>. This is Python telling us that we are in the middle of a code block, and so long as we indent our code it should be a part of this code block. - Press the spacebar 4 times to indent.

- Type

print("Six is greater than five!") - Press Enter to end the line. The prompt will still be a

... - Press Enter one more time to tell Python you are done with this code block. The code block will now execute.

All together, it will look like this:

>>> if 6 > 5:

... print("Six is greater than five!")

...

Six is greater than five!

What is going on here? When Python encounters the if keyword, it evaluates the expression following the keyword and before the colon. If that expression is True, Python executes the code in the indented code block under the if line. If that expression is False, Python skips over the code block.

In this case, because 6 really is greater than 5, Python executes the code block under the if statement, and we see "Six is greater than five!" printed to the screen. Guess what will happen with these other expressions, then type them out and see if your guess was correct:

if 0 > 2:

print("Zero is greater than two!")

if "banana" in "bananarama":

print("I miss the 80s.")

more choices: if and else[edit]

if lets you execute some code only if a condition is True. What if you want to execute different code if a condition is False?

Use the else keyword, together with if, to execute different code when the if condition isn't True. Try this:

sister_age = 15

brother_age = 12

if sister_age > brother_age:

print("sister is older")

else:

print("brother is older")

Like with if, the code block under the else condition must be indented so Python knows that it is a part of the else block.

compound conditionals: and and or[edit]

You can check multiple expressions together using the and and or keywords. If two expressions are joined by an and, they both have to be True for the overall expression to be True. If two expressions are joined by an or, as long as at least one is True, the overall expression is True.

Try typing these out and see what you get:

1 > 0 and 1 < 2

1 < 2 and "x" in "abc"

"a" in "hello" or "e" in "hello"

1 <= 0 or "a" not in "abc"

Guess what will happen when you enter these next two examples, and then type them out and see if you are correct. If you have trouble with the indenting, call over a staff member and practice together. It is important to be comfortable with indenting for tomorrow.

temperature = 32

if temperature > 60 and temperature < 75:

print("It's nice and cozy in here!")

else:

print("Too extreme for me.")

hour = 11

if hour < 7 or hour > 23:

print("Go away!")

print("I'm sleeping!")

else:

print("Welcome to the cheese shop!")

print("Can I interest you in some choice gouda?")

You can have as many lines of code as you want in if and else blocks; just make sure to indent them so Python knows they are a part of the block.

even more choices: elif[edit]

If you need to execute code conditional based on more than two cases, you can use the elif keyword to check more cases. You can have as many elif cases as you want; Python will go down the code checking each elif until it finds a True condition or reaches the default else block.

sister_age = 15

brother_age = 12

if sister_age > brother_age:

print("sister is older")

elif sister_age == brother_age:

print("sister and brother are the same age")

else:

print("brother is older")

You don't have to have an else block, if you don't need it. That just means there isn't default code to execute when none of the if or elif conditions are True:

color = "orange"

if color == "green" or color == "red":

print("Christmas color!")

elif color == "black" or color == "orange":

print("Halloween color!")

elif color == "pink":

print("Valentine's Day color!")

If color had been "purple", that code wouldn't have printed anything.

Remember that '=' is for assignment and '==' is for comparison.

In summary: the structure of if/elif/else[edit]

Here's a diagram of if/elif/else:

Do you understand the difference between elif and else? When do you indent? When do you use a colon? If you're not sure, talk about it with a neighbor or staff member.

Booleans[edit]

Please return to the interactive Python interpreter for the rest of the tutorial. And remember: type out the examples. You'll thank yourself tomorrow. :)

So far, the code we've written has been unconditional: no choice is getting made, and the code is always run. Python has another data type called a boolean that is helpful for writing code that makes decisions. There are two booleans: True and False.

True

type(True)

False

type(False)

You can test if Python objects are equal or unequal. The result is a boolean:

0 == 0

0 == 1

Use == to test for equality. Recall that = is used for assignment.

This is an important idea and can be a source of bugs until you get used to it: = is assignment, == is comparison.

Use != to test for inequality:

"a" != "a"

"a" != "A"

<, <=, >, and >= have the same meaning as in math class. The result of these tests is a boolean:

1 > 0

2 >= 3

-1 < 0

.5 <= 1

You can check for containment with the in keyword, which also results in a boolean:

"H" in "Hello"

"X" in "Hello"

Or check for a lack of containment with not in:

"a" not in "abcde"

"Perl" not in "Python Workshop"

End of Part 2[edit]

Congratulations! You've learned about and practiced executing Python scripts, booleans, conditionals, and making choices with if, elif, and else. This is a huge, huge accomplishment!

Take a break, stretch, meet some neighbors, and ask the staff if you have any questions about this material.